The Vast Majesty of the Amazon Rainforest

Have you ever wondered what it’s like to step into a forest so immense and ancient that it breathes like a living entity?

That’s exactly the sensation the Amazon Rainforest gives — a realm of staggering scale, breathtaking biodiversity, and absolutely critical global significance. In the following article, I’ll take you on a journey through its geography, life forms, human stories, threats, and what the future might hold. I’ll write as if I’ve walked through its green canopies and lightly brushed its misty riverbanks — casually yet with the kind of depth you’d expect from someone who’s spent time pondering its mysteries.

1. Location, Extent and Geological Origins

1.1 The Basin and Its Boundaries

The Amazon Rainforest spans the drainage basin of the mighty Amazon River and its countless tributaries in northern South America. It covers an area of roughly 6 million km² (or more) of dense tropical forest. Geographically, it is bounded by the Guiana Highlands to the north, the Andes Mountains to the west, the Brazilian central plateau to the south, and the Atlantic Ocean to the east.

1.2 Spanning Nations and Shared Responsibility

The Amazon doesn’t belong to one nation — it is a shared treasure. It covers parts of at least eight countries: Brazil (which holds about 60 % of the forest), Peru, Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Bolivia, Guyana, Suriname and the overseas territory of French Guiana. This makes its governance and conservation inherently complex, since political, economic and cultural systems vary widely across its expanse.

1.3 Geological and Climatic Origins

From a geological standpoint, the Amazon basin was shaped over millions of years. The rise of the Andes to the west rerouted ancient waterways and trapped moisture in the lowlands, fostering thick forest growth. Its climate is dominated by high rainfall, high humidity, and generally warm temperatures, creating one of the most stable and productive forest ecosystems on Earth.

2. Ecosystem Structure: Layers, Rivers and Forest Types

2.1 The Vertical Layers of the Forest

Walking beneath the canopy of the amazon rainforest, you’ll encounter distinct layers: the forest floor, the understory, the canopy, and the emergent layer. Each layer supports specialized plants and creatures. Light dwindles as you descend to the forest floor; yet incredible biological activity persists. The canopy itself is like a green ceiling, teeming with birds, insects and vines. Emergent giants push above the canopy to grasp sunlight. This vertical complexity is one reason the Amazon houses such vast biodiversity.

2.2 Rivers, Floodplains and Várzea

Rivers are lifelines in this forest. The amazon rainforest River and its tributaries carve through the land, creating floodplains and várzea forests that seasonally flood. These flooded forests are unique zones where aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems intermingle. The annual flooding brings nutrients, shapes soils, and influences which species thrive where. It’s a dynamic dance between water and forest, one that defines much of the Amazon’s character.

2.3 Varied Forest Types and Micro-Ecosystems

Contrary to a simplistic view of the amazon rainforest as one homogeneous jungle, there are multiple forest types: terra firme (never flooded), seasonally flooded forests, swamp forests, bamboo stands, palm forests and patches of savanna-type clearings. Each type supports its own species assemblage and ecological processes. The mosaic of micro-ecosystems increases overall resilience and richness.

3. Biodiversity: Life Beyond Imagination

3.1 Plants: A Forest of Many Secrets

The amazon rainforest is home to tens of thousands of plant species. Estimates suggest there are upwards of 40,000 plant species here alone. Trees are measured in hundreds of species per hectare in some places. These plants don’t just sit silently—they interact in competition, cooperation (like symbiotic fungi), and support innumerable animals and micro-organisms. And still, scientists believe many species remain undocumented.

3.2 Animals: From Tiny to Enormous

In this lush world, animals of all scales roam, fly, swim and crawl. There are more than 400 mammal species, thousands of insect species, hundreds of birds, reptiles and amphibians. Consider that in a single hectare you might find dozens of tree species, hundreds of insect species and dozens of bird species — a density of biodiversity rarely matched anywhere on the planet.

3.3 Micro-Life, Fungi and the Unseen Majority

Often overshadowed are the microbes, fungi, invertebrates, and soil organisms. Yet they form the foundation of the ecosystem: decomposing matter, cycling nutrients, interacting with roots, shaping soils. The amazon rainforest health depends on this invisible army of life. While we know so much about the macroscopic species, our ignorance of the micro-world is humbling — and it means that every tree and every patch of soil may harbor untold discoveries.

4. Climate Influence and Ecosystem Services

4.1 Carbon Storage and Global Climate

The amazon rainforest is a major carbon reservoir. Its trees store billions of tonnes of carbon, helping regulate the global climate. When forest cover is lost, that carbon is released, and the forest’s ability to act as a carbon sink diminishes. This interplay makes the Amazon critical not just for South America but for the planet.

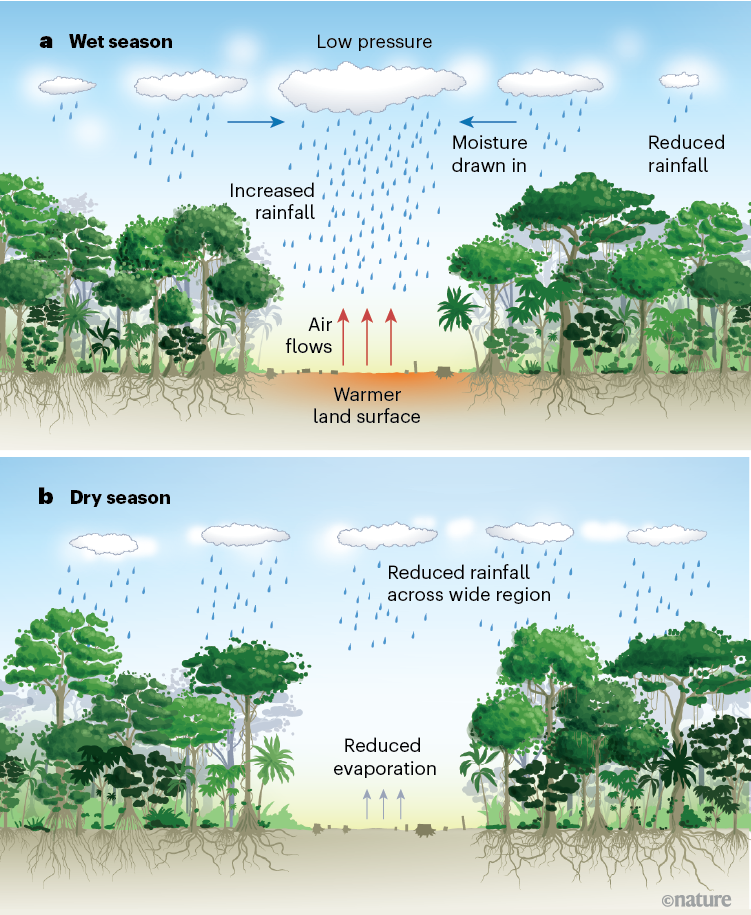

4.2 Rainfall, Water Cycles and “Flying Rivers”

The amazon rainforest supports massive evapotranspiration — trees release moisture into the atmosphere, which contributes to rainfall locally, regionally and even far beyond the forest. These so-called “flying rivers” help sustain rain patterns that benefit agriculture, water supply and ecosystems across South America. Without the forest’s water cycle, rainfall patterns could shift dramatically.

4.3 Soil, Nutrient Cycling and Ecosystem Health

Even though many amazon rainforest soils are nutrient-poor (having been leached by heavy rainfall), the system has adapted: rapid cycling of nutrients through leaf litter, decomposition and root uptake allows this lush vegetation to thrive. Forest loss disrupts those cycles, often making previously forested land less productive. The forest’s ecosystem services include soil stabilization, water filtration, and habitat provision — functions we often take for granted.

5. Indigenous Peoples and Cultural Heritage

5.1 Indigenous Communities and Their Lands

Over thirty million people live in the amazon rainforest region, belonging to hundreds of ethnic groups. Many of these communities have lived in or near the forest for millennia, developing deep knowledge of its rhythms, plants, animals and forces. Their lives are intertwined with the forest: hunting, fishing, gathering, cultivating in ways adapted to the environment.

5.2 Traditional Knowledge and Forest Stewardship

Indigenous peoples often practice sustainable land management rooted in traditional knowledge — using local plants for medicine, crafting shelters from tree species, understanding seasonal patterns, and rotating areas of use. In many cases, regions managed by indigenous communities show lower deforestation rates. This underscores the role of human culture in conservation, not just as a threat but as a partner.

5.3 Culture, Languages and Forest Identity

The amazon rainforest is also a place of cultural richness: languages, myths, songs, and cosmologies shaped by the forest. For many people, the forest is not simply “nature” but home, identity, and heritage. Recognizing and protecting those cultural dimensions is essential in any conversation about conservation. Ignoring them risks both ecological harm and human injustice.

6. Threats and Challenges Facing the Amazon

6.1 Deforestation and Land-Use Change

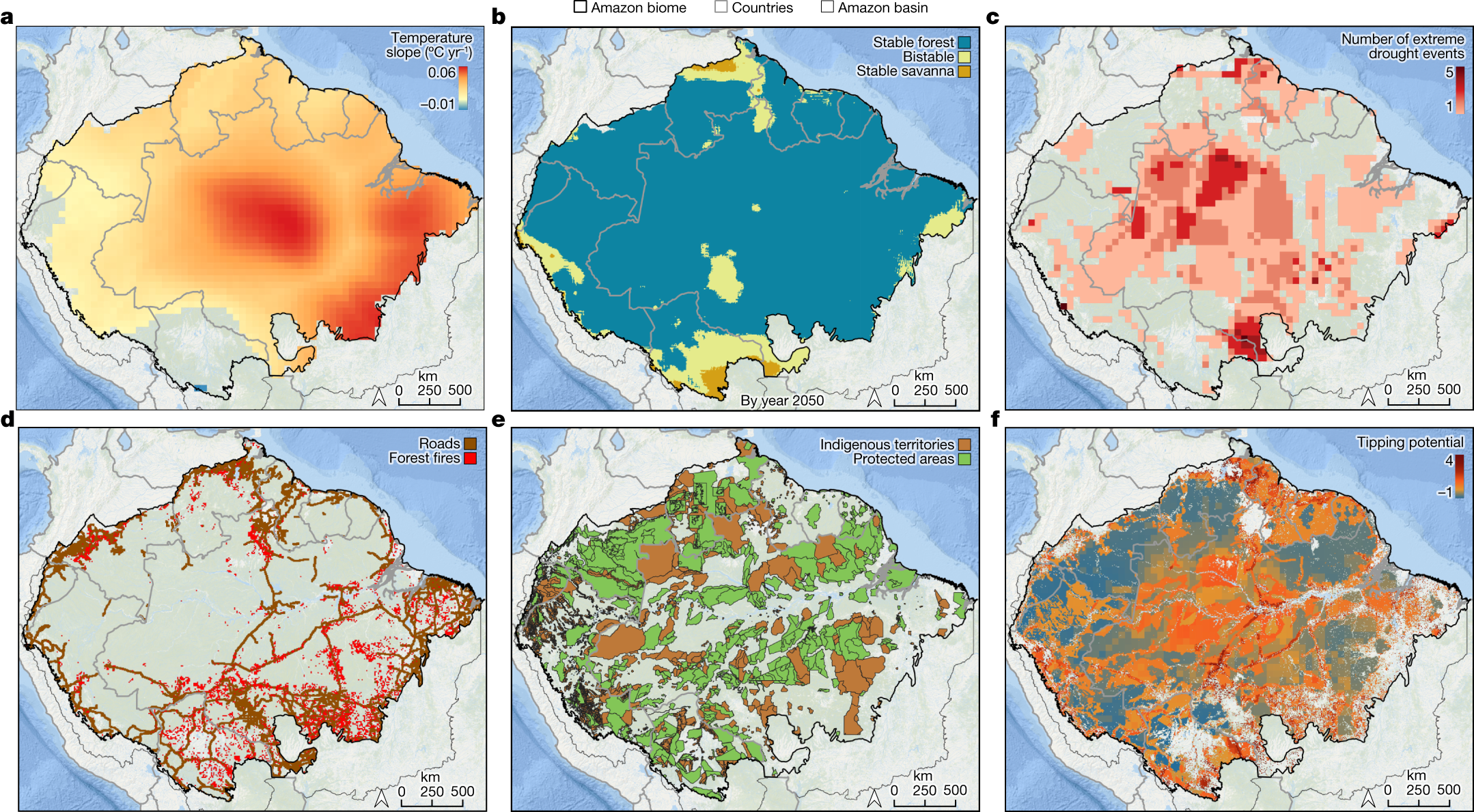

One of the most significant threats is deforestation — clearing forest for agriculture (especially cattle ranching), soy plantations, logging, mining and infrastructure development. According to some estimates, up to 17 % of the amazon rainforest forest cover has been lost in the last 50 years. When forests are cut down, the consequences extend far beyond the cleared trees: habitat loss, carbon release, altered water cycles, and local climate change all follow.

6.2 Fires, Droughts and Climate Stress

While rainforest might seem impervious to fire, under conditions of prolonged drought (exacerbated by climate change), even the amazon rainforest can burn. As droughts intensify, fire risk grows. Some studies warn the Amazon may reach a tipping point by around 2050 if current trends continue. Drought also weakens forest resilience: trees may struggle, regeneration may be slower, and dryness can favor savanna-type vegetation replacing rainforest.

6.3 Infrastructure, Mining and Fragmentation

Roads, dams, pipelines and mines slice through what was once continuous forest. Fragmentation is dangerous: it isolates populations, disrupts animal migration routes, and changes micro-climates at the forest edge (edges are more vulnerable to wind, sunlight and drying). Mining and oil extraction often open the forest to further clearing and illegal exploitation. These human intrusions amplify other threats.

6.4 Loss of Biodiversity and Ecosystem Resilience

As species disappear or ecosystems change, the forest’s network of life becomes weaker. If key species are lost (for example, large trees, seed-dispersers, top predators), the whole system shifts. Some studies suggest that parts of the Amazon have already lost resilience in recent decades. Loss of resilience means the system is less able to bounce back from disturbances.

6.5 Climate Change: A Multiplier of Threats

Climate change doesn’t only bring warming; it brings altered rainfall patterns, longer dry seasons, stronger storms, and shifting ecosystems. For the amazon rainforest, that could mean decreased rainfall, higher temperatures and faster forest degradation—ultimately jeopardizing its role as a carbon sink and rainforest. Some climate models show “dieback” scenarios where large portions of the Amazon convert to less dense ecosystems under severe warming.

7. Conservation Efforts and the Road Ahead

7.1 Protected Areas and Indigenous Territories

Much of the amazon rainforest is now recognised under protection or in legal indigenous territories. These designations help slow deforestation, provide legal frameworks for conservation, and integrate local communities into management. According to one source, indigenous territories occupy more than 300 million acres of the Amazon. Effective protection often means not just drawing lines on the map, but supporting on-the-ground management, enforcement, community engagement and sustainable livelihood alternatives.

7.2 Sustainable Development, Agriculture and Value Shifts

Conservation is no longer just about saying “no” to exploitation, but about providing viable alternatives: sustainable agriculture, low-impact logging, eco-tourism, payments for ecosystem services, and supply-chain accountability. For example, ranching and soy production in the amazon rainforest have been linked to high deforestation; shifting those industries towards zero-deforestation practices is vital.

7.3 Global Partnerships and Financing

Because the amazon rainforest health affects the global climate and biodiversity, its conservation attracts international attention, funding and collaboration. Governments, NGOs, indigenous groups and private companies are increasingly engaged in joint efforts. Without global cooperation, local efforts may face limitations since economic pressures and global markets drive many threats.

7.4 Restoring Degraded Lands and Re-Wilding

Where forest has been lost or degraded, restoration efforts are emerging: planting native species, removing invasive plants, reconnecting habitat patches, and reintroducing species. While restoration cannot replace intact primary forest, it plays a role in improving ecosystem function and providing corridors for wildlife.

7.5 The Tipping-Point Narrative and Urgency

Scientific research increasingly warns that the amazon rainforest may approach a “tipping-point” — a threshold beyond which the forest ecosystem could shift rapidly into a different state (e.g., savanna) with much lower tree density, lower carbon storage and altered rainfall feedbacks. That sense of urgency underscores why conservation efforts must scale up and integrate climate adaptation, not just deforestation controls.

8. The Amazon’s Role in Human Culture, Economy and Science

8.1 Medicinal Plants, Bioprospecting and the Unknown

The forest is a massive reservoir of chemical diversity. Many medicinal plants used by indigenous groups remain under-studied, and scientists continue to explore the potential for new medicines arising from rainforest species. Each lost species may mean a lost medical opportunity. By safeguarding forests, we also protect a library of nature’s solutions.

8.2 Ecotourism, Education and Inspiration

The amazon rainforest inspires wonder. Ecotourism, when done sustainably, offers a way for people to experience the forest, generate income for local communities, and raise global awareness. Lodges, river excursions, guided walks in canopy towers — they all help people connect with the wild. That connection often translates into support for protecting it.

8.3 Research, Observation and the Cutting Edge

Research stations deep in the forest (for example the Amazon Tall Tower Observatory) collect data on atmosphere, soil, vegetation and climate interactions. Such scientific work is vital for understanding how the Amazon works, how it is changing, and how to protect it effectively. It turns the rainforest into a living laboratory for global science.

8.4 Economic Links: Resources, Supply Chains and Trade

The amazon rainforest is rich in natural resources—from timber to minerals to agricultural land. That wealth also creates pressure. Many global supply chains (cattle, soy, timber, mining) are connected to Amazon dynamics. Recognising those links is part of creating responsible trade, supply chain transparency and aligning economic incentives with conservation.

9. What Happens If the Amazon Suffers: A Global Concern

9.1 Climate Feedback Loops and Carbon Release

If the amazon rainforest loses enough forest cover, its capacity to absorb carbon will drop, and it may even become a carbon source rather than a sink. Some studies indicate this shift may already be happening in certain parts. That means more CO₂ in the atmosphere, more warming, and a worsening of the very climate crisis we’re trying to combat.

9.2 Rainfall Reduction, Drought and Regional Agriculture

Without the forest’s moisture recycling, rainfall in the region could decline significantly. That would affect agriculture, hydropower, drinking water and ecosystems across South America. The “flying rivers” might falter, and the consequences would ripple outward. People living far from the Amazon could feel its loss.

9.3 Biodiversity Loss and Extinction Cascades

The disappearance of species in the amazon rainforest would not just mean fewer beautiful birds or strange frogs. It could weaken ecological networks: pollinators decline, seed-dispersers vanish, predators disappear, nutrient cycles unravel. Changes in one part of the system often lead to cascading effects elsewhere.

9.4 Human Lives, Culture and Displacement

If the amazon rainforest degrades, indigenous peoples and local communities will suffer most. Their livelihoods, culture and land rights are tightly bound to the forest. Loss of the forest means loss of identity, food security, water supply and home. The human cost is as real as the ecological cost.

10. How You and I Can Make a Difference

10.1 Conscious Consumer Choices

What we buy matters. If we support plantations or supply chains linked to deforestation, we contribute to the problem. By choosing products certified as deforestation-free, supporting companies with responsible sourcing, and staying informed, we can push demand toward sustainability.

10.2 Supporting Indigenous Rights and Local Voices

Backing organizations that protect indigenous land rights, support community monitoring and empower local stewardship is critical. These people are front-line guardians of the forest and often have the most at stake. Their leadership is invaluable.

10.3 Advocacy, Education and Awareness

Raising awareness—whether through social media, education, local community groups or traveling responsibly—helps build a culture of conservation. When more people from different parts of the world recognise the amazon rainforest value, that builds pressure for policy, funding and action.

10.4 Donations, Scientific Support and Volunteering

Many conservation organisations work directly on the ground: restoring habitat, monitoring wildlife, supporting sustainable livelihoods, building networks of protection. Even small contributions help. If you’re able to volunteer or support research partnerships, that adds capacity and momentum.

11. Looking Ahead: Future Scenarios and Hopes

11.1 Optimistic Pathways: Protection, Restoration and Innovation

It is possible that the amazon rainforest does not simply decline. With stronger protections, smarter land-use, collaboration with indigenous communities, innovation in agriculture and a global shift toward valuing ecosystem services, the rainforest could not only survive but thrive. Restoration efforts and ecological corridors could help reconnect degraded areas.

11.2 The Middle Road: Manageable Risk with Action

If action is taken but incrementally, we might see a slower decline — losses still happen, but managed, with adaptations in place. Some areas may shift in character, but critical ecosystems remain intact. The Amazon would still function as part of the global climate system, albeit under strain.

11.3 Worst-Case Scenario: Tipping Point and Transformation

If current destructive trends continue unchecked, scientists warn of the tipping point: large sections of the Amazon convert to savanna-like ecosystems, drastically reducing forest cover, biodiversity and carbon storage. The Guardian This scenario would have profound consequences, not just locally but globally.

11.4 Our Role in Shaping Which Path We Follow

The future of the amazon rainforest is not predetermined; human choices matter. Policy decisions, economic frameworks, cultural values, global cooperation — they all feed into which direction this ecosystem takes. That means that despite the scale of the challenge, there remains agency and hope.

Conclusion: A Call to Reverence and Responsibility

As I wrap up this exploration of the Amazon Rainforest, I hope you feel both awed by its richness and motivated by its fragility. This forest is not a distant abstraction—it is a living, breathing realm that ties directly into our climate, our culture and our future. It is home to countless species, deep histories, rich human cultures and ecological wonders we are only beginning to understand.

May we recognize that protecting the amazon rainforest isn’t just about saving a rainforest—it’s about preserving the very foundation of life on Earth as we know it. And in that recognition lies both a challenge and a chance: to act, responsibly and compassionately, so that future generations might walk beneath its green canopy and feel the same awe we can only start to feel today.